Will Science Ever Explain Consciousness?

It already has

Substack has a small number of philosophers of mind and one of the best benefits of blogging is that one doesn’t have to wait 6-12 months (if not longer) to publish replies, as one would in the case of journal articles. So it’s a good opportunity to immediately call others out for flawed arguments.

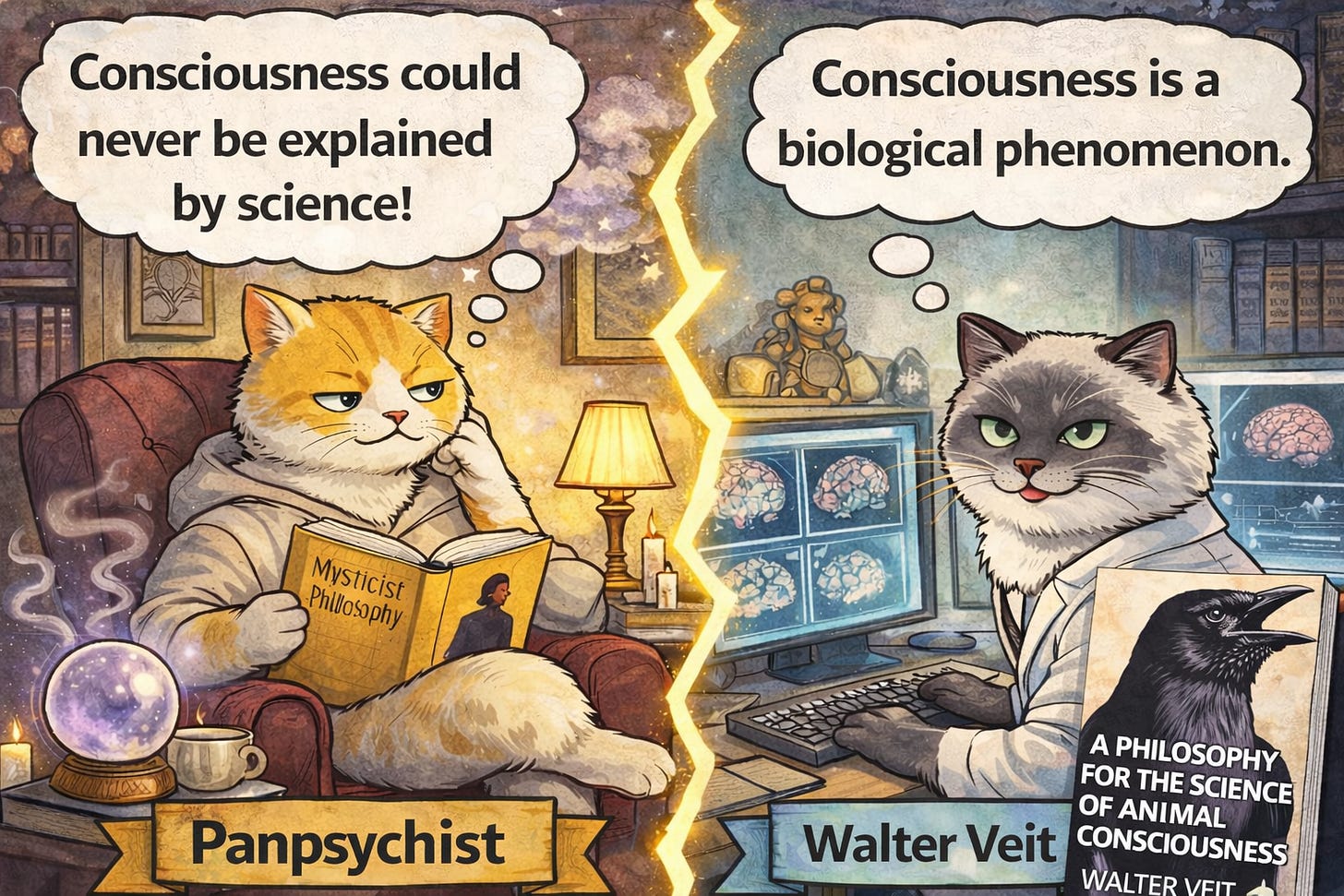

Originally, I started to blog here only to provide easy-to-digest pieces of my new research papers. When I wrote about some of the deeply problematic philosophical assumptions behind panpsychism that I criticized in my latest journal publication my readership exploded, but the comments also forced me to explain many common misunderstandings about the relationship of philosophy and science. Yesterday, I posted a popular essay on some of the deeply anti-Enlightenment a priori metaphysics that characterizes the anti-science sentiments of many philosophers, not just panpsychists. With perfect timing Goff posted a new short blog post today, titled Will Science Ever Explain Consciousness?, in which he argues that it’s a category error to think that science can ever explain consciousness.

I will go into his arguments to not only reveal how they reflect very troubling assumptions, but also to argue that consciousness has, in fact, already been explained. Let’s begin.

Goff starts by stating that:

Consciousness is not just another scientific problem we haven’t dealt with yet. We won’t be at first base on this issue until we’ve appreciated the unique nature of this challenge.

Always good to start with a truism that anyone could agree with. Consciousness, any scientist would be happy to acknowledge, is a complex phenomenon and this complexity should be appreciated, but - of course - Goff wants to say more than that.

What is so special about consciousness? It’s special because we have direct access to the phenomenon we’re trying to explain. Each of us is directly aware of our feelings and experiences. This direct access provides information about the nature of these states: A pain is defined by how it feels, and you know how it feels when you feel it. Moreover, this is information about the nature of our conscious states that can’t be discerned from experiments.

Fair enough, we have a kind of access to consciousness that we lack in terms of what goes on in Mars or the Deep Sea. But direct awareness is quite a bit overstated when philosophers start to fetishize it. People are actually pretty bad at characterizing their own experiences and there is plenty of research showing that people misrepresent them, e.g. vision or memories. So the emphasis many philosophical opponents to scientific explanations of consciousness put on the “direct knowledge” is playing with the ambiguity between the fact that we have subjective experiences and the much stronger claim that this access is more significant than anything coming out of consciousness research. We do not have infallible knowledge even about our own experiences and certainly not about the “nature of our conscious states” across all other humans or animals.

A blind from birth scientist isn’t going to learn what it’s like to see red from reading about the physical processes associated with colour experience. This is totally different to any other phenomenon science seeks to explain. Is lightening the anger of the gods? Is water a fundamental element, alongside fire, earth, and air? We have absolutely no idea what these things are until we do the science. But with consciousness, we have significant knowledge of its nature prior to doing science, and this is knowledge that can’t be got from the science.

Goff mistakingly claims that our own experiences give us knowledge of the nature of consciousness. But that’s simply false. At best his introspective analysis of his own experiences tells us something about his form of consciousness, but one needs to be careful not to overgeneralize this. As I’ve argued in my book A Philosophy for the Science of Animal Consciousness, claims about the nature of consciousness by philosophers routinely make the embarassing error of equating human consciousness with consciousness as a natural phenomenon that spreads far across the animal branch of life. And the diversity even within our own species is radically underestimated.

Doesn’t having some extra knowledge “from the inside” make the problem of consciousness easier? In a sense, perhaps. But it also means we end up with a very different explanatory project compared to what we’re normally doing in science. Standardly in physical science the task is to explain structure and dynamics: what stuff does. When we explain the phase change of water, for example, we’re explaining why water behaves in a rigid manner when frozen, more flexibly when melted, and then floats around when boiling. We explain this behaviour in terms of the behaviour of the molecular components, e.g. how strong the hydrogen bonds are.

This description of science is simply wrong. Firstly, Goff exhibits a radical and naive reductionism according to which an explanation of consciousness must be given by physics, rather than neuroscience, which is of course absurd and part of the reason panpsychists want to radically change physics itself to make subjective qualia part of it. Consider how Goff continues his argument:

When we’re seeking to explain consciousness, however, we’re not trying explain what stuff does. We’re rather trying to explain the subjective qualities we immediately apprehend in our experiences. We’re trying to explain why a system feels a certain way, not why it behaves a certain way. This is not to deny that feelings and behaviour are closely connected; pain causes us to scream and try to get away. The point is just that when I ask “Why is my wife feeling pain?”, I’m not asking about why she’s behaving in a certain way, or why some of her parts are behaving in a certain way. I’m asking why she’s feeling a certain way, and that’s just a different question. Of course, in the practical course of life, part of the answer to “Why is my wife feeling pain?” may be that she’s in certain physical states. But if we’re doing philosophy and digging down to foundations, this leads quickly to the question: “Why are those physical states correlated with feelings?”

Here Goff exhibits an unfortunate dualism that naturalistic philosophers of mind have worked hard to overcome. It’s due to the unfortunate influence of analytic metaphysics that some scientists have started to talk about neural correlates of consciousness as if consciousness was some magical property produced by the brain separate from the material and cognitive processes of the brain.

The gap between our experiences and what science can tell us about what goes on in our brains is no more puzzling than the gap between physics and the folk ontology of tables or the connections between any of the special sciences. Curiously, Goff simultaneously aims to be anti-scientistic while endorsing radical reductionism. One cannot have it both ways. If a complete reduction of phenomenology to physics has failed, then so have all other special sciences. And yet, Goff is not denying that these sciences commit category mistakes.

On the other hand, despite the inevitable gaps in our understanding of the world, the question of why someone is feeling pain can indeed be answered by recourse to the biological sciences.

To answer why things feel bad is ultimately answered by the evolutionary question of how such experiences enhanced the survival chances of biological entities. The same goes for other forms of experience as I have argued in my book and elsewhere. Indeed, we have made great progress on these questions. We can legitimately say that science has already explained why animals feel pain. It’s no mystery that would require us to postulate qualia as a basic building block of reality itself.

The idea of a physical explanation of consciousness makes no sense upon reflection. It’s a category mistake. This is important because it’s common to hear the following: “Physical science has done brilliantly historically, of course it’s going to explain consciousness.” To my mind, this is like saying, ‘“Telescopes are fantastic for looking at the stars, surely that shows they’ll be brilliant in pure mathematics!” Physical science is amazing at explaining what stuff does. But trying to explain why something feels is just a different explanatory project.

Let me quickly add: Physical science is crucial for making progress on consciousness. We need science to establish which kinds of conscious experience go with which kinds of brain activity. But the question of why physical reality and consciousness are tied together in the ways science reveals is a philosophical rather than an experimental question.

In other words, we need both science and philosophy working in hand in hand to make progress on consciousness.

This is an artificial separation of philosophy and science. Scientists are not just engaged in counting peas. And the romantic vision of philosophers working together with scientists is, in fact, a view that Goff rejects. “Science and philosophy working in hand in hand” is exactly what naturalistic philosophers like Dan Dennett and myself have been doing. What Goff is actually defending is a separate domain of philosophy upon which science has no say at all. That it’s a “category mistake.” This is not working together. It’s really saying that philosophers are the only ones who can study the nature of consciousness.

All of this would be more promising if anti-naturalist philosophers like Goff could at least point to a handful of insights that such a separate form of philosophy of mind has provided us about the nature of consciousness.

But there are none to speak of…

Talk of alternative explanatory projects is interesting until one realizes that this all so promising project has not offered us anything at all. Just like hopeful patients suffering from cancer may be duped into pseudoscientific alternative medicine, who may regretfully come to realize at the end of their lives that the arguments against the traditional approach may have been all smoke and mirrors - so too with the arguments against a science of consciousness.

While we have no agreed upon final grand theory of consciousness yet, there are no such agreements for other complex phenomena such as cancer, immune systems, or the economy either. Yet, these domains are no longer unexplained mysteries. Consciousness, likewise, is actually already well-explained with much consensus about the advantages of different types of experiences. And these are just the why questions Goff insists that only introspective reflection by philosophers from the armchair could ever solve.

If you enjoyed reading this post please like, share, and subscribe. It helps a lot to reach a wider audience. I am also interested to read your thoughts in the comments, regardless of whether you agree or disagreee. I try to respond to all.

Thanks Walter. There are two aspects to my argument. One concerns what we know about consciousness "from the inside". The other concerns the nature of physical science explanation. You put the two together to get my argument that we can't completely explain consciousness via physical science explanation (although of course physical science has a crucial role to play).

Let's just focus on the first bit. You are ascribing to me two things I don't think: (i) that are introspective beliefs about consciousness are infallible, (ii) we know from the inside the nature of consciousness in all creatures. I'm happy with with you to reject these two things.

But what about my claim that a blind from birth neuroscience will never know what it's like to see red. Isn't this something about the nature of that specific experience that cannot be discerned from third-person science?

“To answer why things feel bad is ultimately answered by the evolutionary question of how such experiences enhanced the survival chances of biological entities.” That gives an explanation in terms of historical origins, not in terms of the intrinsic nature of the experience itself (a property which is presupposed by your evolutionary explanation). So you haven’t explained what really needs explaining.