Why Effective Altruists (And Everyone Else) Should Become Nihilists

Reclaiming Moral Nihilism

I have no doubt that this may be my most controversial post yet (if not ever). For I will try to convince you to become a moral nihilist, not just because it is the best metaethical position, but because I will argue that morality itself is bad, and we could have a better, more altruistic world without it.

Now to claim that morality is bad will immeditaly strike some as an oxymoron. “If there are no moral facts then how can morality be good or bad? Gotcha!” Please bear with me for a moment before you decide that this view is obviously absurd and incoherent. (If you still end up disagreeing, please explain your reasons in the comment section.)

Since I have published many articles in ethics, share close affinities with the goals of effective altruism as a self-avowed utilitarian, and spend much of my time advocating for the better treatment of other animals, people are often surprised to learn that I consider myself a moral nihilist and do not believe in moral facts. On the faces of many interlocutors I can see puzzlement. These views seem strikingly inconsistent and a philosopher should not hold such obviously inconsistent beliefs. Sometimes I received the odd hostile squint, or angry comment online, suggesting that it is dishonest to engage in ethical argumentation while thinking that there are no objective moral truths.

Yet, this attitude turns out to be remarkably widespread. Many philosophers will have experienced it in their classrooms. Students cling to nihilistic stances while also seemingly holding strong moral convictions about how our society should be organized. It is tempting to dismiss this as a common mistake among first-year undergraduates, but moral anti-realism is a widely shared view even among effective altruists who have spent more time than most thinking about how they can do good in the world and what that means.

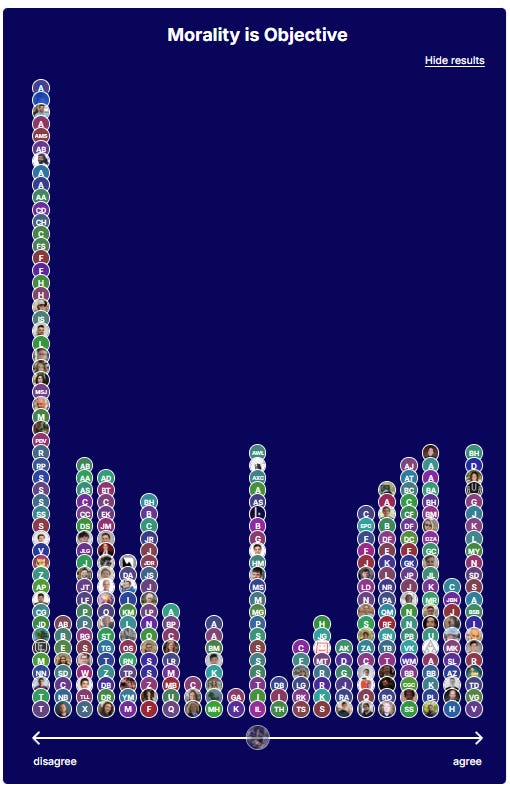

In a survey on the Effective Altruism Forum initiated by Bentham's Bulldog, members were asked to place themselves on a continuum in response to the question “Is Morality Objective? Yes or No.” The result of 312 votes was heavily skewed towards anti-realism, which may surprise some readers:

Yet, despite this result the survery was likely biased towards moral realism, because the survey opened with a long argumentative essay by Bentham's Bulldog against moral anti-realism concluding with this statement:

Moral anti-realism is certainly an internally consistent position. But it’s a very implausible one. It gives up many of the most obvious truth about the world—the stance independent wrongness of torture—on the basis of super lame arguments. Absent some extremely compelling reason to accept it, we should remain convinced that it’s false. Some things really are wrong.

Given how easy it is to push my students to vote for one view over another in virtue of how I frame the question and options, I was actually surprised by how many ended up voting for an anti-realist view about ethics. The forum post included 220 comments, with arguments for and against moral anti-realism, for instance by Richard Y Chappell who I have previously featured on my podcast and defended moral realism. It is ironic that despite close agreement on first-order issues, effective altruists are so split on meta-ethics. One might have expected the altruistic sacrifices of effective altruists to have been motivated by a conviction in moral facts. Yet, many appear to be nihilists. Now, I will note that few moral anti-realists will adopt the label of ‘moral nihilist’, which is historically associated with a kind of destructiveness and lack of concern for others, not unaided by the ironically also German nihilists in The Big Lebowski.

But I am using the term in a neutral sense that allows any moral nihilist to also be among the most altruistic people on this planet. All it requires is a denial of moral facts. The prominent effective altruist and Harvard psychologist Joshua Greene has even written a book for why this kind of nihilism supports a first-order embrace of utilitarianism.

See this interview of him on the Lives Well Lived Podcast by Kasia de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer:

Like Greene, I think utilitarianism—of all moral theories—is the least like the castles in the sky that moral philosophers have built. Even if there are no moral facts, pleasures and pains still exist, as do preferences. Things can still be better or worse for humans or other animals from their own point of view, irrespective of whether morality exists. And we can, of course, care about these interests. So effective altruists aiming to do “more good with their time, money, and resources” need not be comitted to morality at all, if it just means to promote the interests of people. The idea that things can’t be ‘good’ for someone from their own point of view, unless moral realism is correct, is a common error comitted by philosophers. When I speak of nihilism enabling a better world, I don’t imply any objective evaluation of the world in moral terms, just that individually we would be better of and should prefer it on pure prudential grounds.

Indeed, it is arguably moral nihilism that has motivated a large proportion of effective altruists to join the movement. Morality can be a source of complacency, creating a wide gap between permissible and impermissible actions. As long as you do not violate anyone’s rights or cause them harm, most people think you are free to do whatever you want. At worst, morality doesn’t just make us blind to the suffering of others, but it may even encourage it. Yet, if it is up to us to change the world as we see fit, one may become far more altruistically motivated to shape it in ways we would like to see. Even Peter Singer himself started out as a moral anti-realist.

Of course, I am not denying that an embrace of nihilism may promote selfishness in some individuals. But it is a mistake to think that there is a necessary link here. If you have an altruistic pro-social psychology, none of that will change if you become a nihilist. Indeed, I am willing to make a prediction that psychological studies would show nihilists to have greater altruistic tendencies than the rest of the population, which would also support the survey results among effective altruists.

On that note, I did a podcast episode with the EA-aligned experimental psychologist Matti Wilks, who has also worked with fellow substackers Paul Bloom and Lucius Caviola, on the psychology behind effective altruism and pro-social tendencies like compassion for animals that I can only recommend:

The fear that an adoption of moral nihilism would lead to the end of cilization, however, is a simple mistake. Just like Christians were mistaken to think that atheists could not act altruisticly, we make the same mistake with nihilists, prematurely dismissing the view out of fear of its consequences. And if we can make a case for morality by appealing to its positive consequences… then the door is also opened to do the reverse.

If things can be better or worse for individuals, independently from morality, then we are free to ask whether morality itself is harmful. Indeed, counterintuitively, morality itself might be to blame for many of the greatest ‘evils.’ One of the most obvious cases here is our treatment of other animals. Many of my readers, like myself, greatly care about animal suffering. Yet, as I have argued in an interview for the sentientism podcast by Jamie Woodhouse (see below), morality has historically been used to justify causing harm to them.

Moral arguments often obscure the reality of suffering on the ground. They are frequently detached from reality and can do more harm than good. It is all too easy to cherry-pick the cases where moral arguments had a positive effect to conclude that morality itself must be a net positive. It’s easy to think that our own values reflect some objective way the world should be. And such confidence is not condusive to creating a well-functioning society full of members with radically different interests.

A while ago I wrote up a long case for moral nihilism in a journal article (see here). I was trying to convince people take moral nihilism seriously a real view, rather than a mere straw-man. In The Big Lebowski a character expresses the view that nihilists are even worse than Nazis:

“Nihilists... F#$% me. I mean say what you will about the tenets of national socialism dude, at least it’s an ethos”

I think the opposite is true. An ethos does not have intrinsic value. An ethos can do more harm than good. Perhaps a better world is in reach once we abandon moralistic language and thinking. But to make this point, we first have to reclaim the term ‘nihilism’ not unlike to how the terms ‘queer’ or ‘gay’ started out as pejoratives.

Because I wanted to reach the public, I wrote my article in a deliberatedly accessible style, but of course no non-philosophers read articles from philosophy journals. So I have reposted it here. The royal “we” used throughout is doing a bit of ironic work here, borrowing the voice of universal moral authority employed by kings, prophets, and moralists in order to question whether such authority exists at all. I hope you will enjoy it and I am looking forward to your comments on whether we should abandon morality for a more altruistic world:

Reclaiming Moral Nihilism

If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion. – David Hume

1 Introduction

Ever since John Leslie Mackie (1917–1981) ‘popularized’ moral error theories in meta-ethics - to simplify a bit: theories asserting the falsehood of all moral discourse due to the non-existence of moral properties or facts - increasing attention has been given to how to escape the force of moral nihilism. For many adversaries of the moral error theory (or rather - moral error theories; for there are a variety of arguments for why moral discourse is flawed), ‘moral nihilism’ is used as a derogatory synonym, associated with immorality and selfishness. This makes it similar to the way ‘existential nihilism’ is associated not only with the denial of meaning but also with suicide and harmful behaviour (Veit 2018). But such a defamatory usage of the label is obviously not very helpful for a serious philosophical examination of the view, which is why it is rarely used by those endorsing views that may well appear ‘nihilistic’. Indeed, the goal of this paper is to turn ‘moral nihilism’ from a term of abuse to a ‘badge of honour’, similarly to how the queer community has done so for the word ‘queer’.

Yet, while the term ‘nihilism’ originates from the Latin word nihil for “nothing”, this does not at all provide it with a clear and precise meaning, and it is thus unsurprising that the term ‘moral nihilism’ is used ambiguously by philosophers and laypeople alike. We will therefore begin our defense of moral nihilism by drawing on Richard Joyce’s (2013) International Encyclopedia of Ethics entry on nihilism, to distinguish between at least three different senses that can be given to moral nihilism; a distinction that will help us to clarify the view we are defending.

Firstly, we can treat it as a synonym for the moral error theory, as the second-order view in which “moral discourse consists of assertions that systematically fail to secure the truth” (Joyce 2013, p. 1). Such a view is endorsed for instance by Sommers and Rosenberg (2003) who provocatively promote the label of ‘nihilism’ without thereby implying immorality: “To be an ethical nihilist commits one to nothing more than the denial of objective or intrinsic moral values and categorical imperatives” (p. 668). A moral error theorist could be just as ‘moral’ as any non-nihilist in the sense of engaging in altruistic behaviour and the avoidance of harming others.

Secondly, Joyce (2013) notes that we could treat moral nihilism as the broader second-order view that denies the existence of moral facts, which would also cover various non-cognitivist views on morality that deny that moral discourse is even trying to express facts. Thus, for the non-cognitivist, moral language is more akin to “veiled commands or expressions of desire” (Joyce 2013, p. 1). Like Joyce, however, we think that this expanded meaning is too broad since few non-cognitivists would endorse the label of nihilism for their own.

Nevertheless, we can recognize that these two senses of moral nihilism are second-order anti-realist views in metaethics and do not inherently demand any commitment to another kind of moral nihilism on a first-order level. Such a first-order nihilism can be equivalently referred to as ‘moral eliminativism’ or ‘moral abolitionism’: i.e. the view that we should cease using moral language and thought (see Garner 2007). Rather than thinking of this stance as necessarily implying immoralism (the implication that anyone holding this view would act in ways held in contempt by any of our favorite theories of ethics), we might better describe it as amoralism - i.e. the absence of moral thought and language without thereby implying any other particular actions. We do not see any argument for why an endorsement of nihilism must in any way entail selfish behaviour. A moral nihilist in this first-order sense may likewise well be extremely altruistic. Indeed, we shall later present arguments for moral abolitionism that do not inherently depend on an endorsement of second order moral nihilism, but rather on collective self-interest and altruism. This is plausibly why Joyce (2013) describes moral abolitionism more narrowly as the position that “we should stop using positive moral language” (p. 1), which would fit with, say, an agent maintaining their utilitarian second-order beliefs while advocating for the elimination of moral language to increase aggregate wellbeing.

The way we will here defend ‘moral nihilism’ is as a combination of a second-order error theory regarding moral discourse and a first-order eliminativist stance, or as we may call it: second-order and first-order moral nihilism. This view comes the closest to a charitable and non-derogatory public use of the term ‘moral nihilism’ and it captures the obvious links between a first-order and second-order nihilism. For many error theorists, who think moral discourse refers to non-existent moral facts, this combination of views appears to be at least the most coherent conclusion - akin to how the realization that there are no witches led to the end of witch-talk, or how atheists stop talking in terms of God or praying to a non-existent entity. Simon Blackburn (1993), for instance, notes that if Mackie is right “that our old, infected moral concepts or ways of thought should be replaced” (p. 149).

Yet, both Mackie (1977) and Joyce (2001), alongside other moral error theorists who admit the immediate force of moral eliminativism, do not advocate for the abolition of moral language. Whereas Mackie (1977) is engaged in a kind of Humean reconstruction of morality that tries to rid it of its metaphysically problematic components, Joyce (2001) advocates a fictionalist stance in which we maintain moral discourse as an untrue but useful fiction for the purposes of pursuing our ends - reminiscent of Hume’s instrumentalism regarding reason. Yet, despite the reverence of both for Hume, other moral error theorists such as Ian Hinckfuss (1932–1997) and Richard Garner (1936-2020),[1] who see themselves as standing in a similar intellectual lineage as Hume, advocate the abolition of moral talk - thus raising the question regarding the proper Humean response to the moral error theory. This problem is also known as the ‘now what’ problem of the error theory (Lutz 2014), i.e. what we should do after having accepted it.

Thus, far from being a straightforward matter, the connection of first-order and second-order moral nihilism requires philosophical defense. Here, we shall argue that discarding morality to the flames is the right Humean move to make; a position Joyce describes as being “nihilistic twice over: endorsing a metaethical nihilism (in virtue of being an error theorist) accompanied by a kind of practical nihilism (in virtue of being an eliminativist)” (Joyce 2013, p. 1). Not only do we think that this combination of views is the most philosophically defensible, but also that it best captures the ordinary folk understanding of moral nihilism as view that entails both second-order and first-order commitments.

Article Outline

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we draw on Joyce’s arguments, alongside those of other error theorists for second-order moral nihilism, to defend the view that a Humean conception of reasons is incompatible with the alleged special normative force of morality, and that there is no sense to be made of categorical imperatives within the Humean framework. In Section 3, we move towards consideration of moral talk and argue that Humeans should also be first-order moral nihilists, in addition to examining the practical implications of this position. Finally, in Section 5 we conclude our discussion and explore some further directions for future investigations.

2 The Humean Case for Second-Order Moral Nihilism

As elusive as the phenomenon of morality may appear and as little agreement there is about both first-order and second-order issues, there at least appear to be some ought-statements that approach near consensus. We might, for instance, mention the moral judgement that ‘one ought not to torture babies’ or ‘one should not kill others to accumulate riches’. While some might maintain that such actions could hypothetically be justified if they saved more lives, such cases are certainly hard to imagine, providing us with at least a quasi-exceptionless rule to obey.

Yet, morality is not just like any kind of set of rules. While legal and moral arguments are certainly often confused, we can straightforwardly recognize a difference between a law in Nazi Germany and a moral rule - even if they overlap in content, such as the rule that one ought not to kill one’s husband or wife. What the latter has and the former (or for that matter any legal rule) lacks is a special kind of authority of ‘ought to be followed’-ness that we associate with morality. As Joyce (2001) notes, we do not simply absolve Nazi war criminals from their crimes (p. 98). The oughts of morality are inescapable; they are not like any other rules.

So it is unsurprising that many want to resist moral nihilism - or for that matter moral relativism, as the view that what one is morally required to do depends on the moral norms of one’s society or culture - as positions that can deny that there is an inherent difference between someone following our twentieth-first century moral norms and a Nazi following orders in 1941.

Without morality, it seems, we do not have a justification for calling out the behaviours we deem to be ‘wrong’. Moreover, this special kind of authority persists even in the absence of enforcement and punishment (Joyce 2001). Why this kind of special force is so important for morality is perhaps best encapsulated in the rise of atheism. People feared (and many still do) that atheism undermines the authority of morality, which according to them can only come from God. As the famous dictum (often attributed to Dostoyevsky) goes: “if God is dead, then everything is permissible”. Though this argument is a minority view in moral philosophy, it is commonplace in religious circles, who place the cause of supposed moral degeneration in people turning away from religion. This paper agrees to the extent that without a God as the source of this special authority, Humeans are indeed committed to moral nihilism, though not as straightforwardly as is perhaps expected.

Morality, Practical Rationality, and Normative Reasons

Despite providing us with a set of rules, most people do not treat Nazi law as providing us with normative reasons, but rather what Joyce (2001) calls institutional reasons. To offer a simple explanation, the number of institutional reasons foisted upon us could be infinite, for anyone could come up with a new system of rules, but it is only in virtue of endorsing these rules or by having consequences associated to their adherence that they have normative force upon us. If your four-year old daughter comes up with rules for a new game, these rules will have force upon you if and only if you chose to play the game. Normative reasons are different for they inherently have normative force to them. If you don’t care about the rules of checkers or the rules of etiquette, you might not have a normative reason to stick to them. Similarly, the institution of law might have normative force upon one in virtue of being detrimental to the pursuit of one’s life’s goals if one ends in prison.

For Christians, morality is admittedly very similar to the normative reasons provided by the law. Adherence to the moral code of Christianity promises eternal bliss, whereas a breaking of the rules can lead to eternal punishment, effectively making the institutional reasons of the God-given rules of conduct outweigh the prudential force of all other reasons. In such a religious picture, acting morally is simply the rational thing to do. Without a God in place, however, things are less straightforward.

According to the most recent philpapers survey of 1785 philosophers (see Bourget and Chalmers 2021), it appears that the majority of philosophers (at least in the Anglo-sphere) are atheists, and yet, many moral realists continue to think that the normative force of morality doesn’t just evaporate in the absence of an enforcer. Moral error theorists, however, are deeply skeptical of this idea. As Lutz (2014) puts it: “a moral error theorist will regard any claim to the effect that something should be done, full stop, with suspicion” (p. 352). What the moral nihilist denies is the truth of an utterance like “You ought not to kill your husband” full stop - i.e. that there is nothing more to say, or that it forms as Kant would say: a “categorical imperative”. No reference to the goals of the addressed person is necessary for the proposition to be true. In fact, they are largely irrelevant. According to Joyce (2001), it is this special authority - i.e. the transcendence of the reasons given by morality - which holds even when speaking from outside of it (pp. 39-45).

This is what makes moral facts ‘queer’ according to Mackie (1977). As Garner (1990) notes: “Moral facts are not just unusual in the way that facts about quarks and black holes are unusual, they are unusual in an unusual way–they demand” (p. 143). Similarly, Philippa Foot (1972) criticizes Kantians for relying on an “illusion” as they imbue the oughts of morality with some kind of “magic force” providing authority (p. 315). This magic force it turns out, is necessary for moral facts, and is something that cannot be granted by Humeans. As we shall see shortly, for a Humean, there cannot be a normative reason to act morally if you do not endorse the rule, do not care about it, and there is no punishment in violating it.

For Kantians such as Korsgaard (1996), practical rationality is the solution to this magic force, as the special authority provided by reason for telling you how you ought to act cannot be intelligibly questioned. Practical rationality, as we will use it throughout this essay, is the only source that could possibly justify a judgement like “You ought not to torture babies” full stop. As Joyce puts it: “to question practical rationality is unintelligible – it is to ask for a reason while implying that no reason will be adequate” (2001, p. 50). If one asks why one should act in accordance with the requirements of rationality, then the agent simply does not understand the concept of practical rationality or, worse, may cease to even be an agent (Kolodny 2005). If one asks why one should not torture babies, the answer must provide a normative reason, i.e. a practical reason which shows that torturing babies is necessarily irrational.

In this picture, the source of the authority of morality is ultimately practical reason, making its normative force no longer mysterious. For moral rationalists, morality is then simply a subset of the requirements of practical rationality (see Joyce 2001; Kolodny 2005). Otherwise, morality is just one normative system among many, without any sort of special authority. The problem for this move, however, is that it must ultimately fail to justify categorical imperatives, since there is no eternal punishment that could outweigh all the other reasons an agent might have given their desires and goals in life.

What moral error theorists like Mackie and Joyce have in common with Kantians, or for that matter Christians, is the recognition that moral judgements refer to some kind of authority that one cannot escape from. For both, this categorical authority or universality is what the objectivity of morality entails. Therefore, for every ought-statement (i.e. for every categorical imperative), both defend the following premise that Joyce (2001) calls ‘Mackie’s Platitude’: “MP: it is necessary and a priori, that for any agent x, if x ought to Φ, then x has a reason to Φ” (p. 38).

This is why Kantian categorical imperatives capture moral discourse so adequately. If there was a criminal who tortured innocent children then we would neither want to say that their act was merely wrong according to some institution of rules – as that would make morality no different from etiquette - nor would we want to accept the wrongness of our moral judgement if they claimed on trial that their one and only goal and pleasure in life was to torture innocent people. Joyce (2001) refers to this as the moral rationalist’s “metaethical dilemma”; “[o]ne horn is alienation of an agent from her normative reasons, the other horn is moral relativism” (p. 80). While the first horn makes turns the agent into some sort of slave to the special authority of morality, the second horn eliminates the inescapability of morality by citing different desires.

Admittedly, practical rationality turns us into a similar kind of ‘slave’, but it is instead an enslavement to our own goals. Hence it is not inescapable in the same way, because to any claim of irrationality against our actions we can respond that we simply have different goals than those our critic might have postulated for us. Kantians, however, maintain that there are categorical imperatives that apply for all agents irrespective of their set of motivational states. Yet, it seems hard to justify even a single such moral imperative that would apply to all agents and Kant seems to recognize as much - at least initially. As Joyce hints at, even Kant (1783) himself could have espoused a moral error theory had he adopted a different conclusion: “although we leave it unsettled whether what we call a duty may not be an empty concept, we shall still be able to show at least what we understand by it and what the concept means” (p. 84) [quoted in Joyce 2001, p. 38]. To answer the question of whether categorical imperatives can be made sense of within a Humean picture, we require a more thorough understanding of normative reasons within a Humean framework.

The Humean Theory of Reasons and Inability to Justify Categorical Imperatives

Hume’s theory of reasons is what Joyce (2001) calls a Humean instrumentalism, i.e. “the view that a person has a reason for performing an action if and only if doing so promises to satisfy that person’s desires” (p. 52). It is an instance of what Parfit (1984) described as Instrumental Theories of practical rationality that do not make substantive commitments regarding the outcomes of rational deliberation. Whatever an agent has the most reason to do is relative to the agent’s desires.

Perhaps the most prominent defender of this view among Humean philosophers is Bernard Williams, who is described by Smith (1994) as defending the view that the “desires an agent would have if she were fully rational are themselves simply functions from her actual desires” (p 165). Notably, not all Humean philosophers defend this view - and this includes Smith (1994) himself, who agrees with the Kantian view that morality should be understood as a set of categorical imperatives. But since - as we shall shortly show - these cannot be obtained under a Humean conception of reasons, Smith tries to replace the Humean view with an anti-Humean one in which the normative reasons of all agents would converge upon rational deliberation. While Smith’s view still maintains a link to an agent’s desires, the “lack of convergence among agents’ normative reasons” is abandoned as a central Humean commitment (Joyce 2001, p. 78)

Why, however, does the Humean conception of normative reasons deny the Kantian claim that fully rational agents would converge on the same principles? The reason is that, in the tradition of David Hume, even though Humean philosophers like Williams and Joyce allow for the rational appraisal of aims, this appraisal hinges crucially on the rational deliberation of an agent in relation to their goals. No substantive claims are made about the intrinsic rationality or irrationality of aims; such judgements follow procedurally. Parfit (1984) would have called such Humean accounts of practical rationality a Present-aim theory of rationality which proceeds from an agent’s desires and aims or his motivational set (see Williams 1981, p. 102) to the rational appraisal and justification of desires, aims and actions. Interestingly, Parfit allows for a further qualification under the “Critical-Present aim theory” which opens up the possibility of pre-defining some aims as intrinsically irrational (pp. 92-95). This latter view obviously is not a route a Humean can take, given that irrationality is dependent on an agent’s mental states. The present-aim theory, however, allows for quite sophisticated accounts one may not associate with simple forms of instrumentalism, as one’s normative reasons must not directly satisfy a desire - they are just contingent on them. What rational deliberation, or practical rationality, conceptually entails shall not concern us. As long as the non-convergence of an agent’s normative reasons is safeguarded, the floodgates to second-order moral nihilism have been opened.

Nevertheless, the Kantian claim – that rational deliberation necessarily ends with the same categorical imperatives and, thereby, non-relative normative reasons – cannot be made without already having substantive assumptions about the nature of practical rationality. For the Humean there either is no practical rationality to begin with, or practical rationally is merely contingent on an agent’s mental states regarding what normative reasons he is endowed with. While the former view is a direct denial of reasons for action,[2] the latter view leads most Humeans (like Williams) to some form of moral subjectivism, denying a metaphysically special authority of morality.

For any given categorical imperative of morality that is supposed to hold for every agent regardless of his aims and desires, Humeans could postulate an agent who does not have a normative reason to adhere to such a principle. Take the example of a man torturing babies: the Kantian wants to say that a fully rational version of that man would conclude that he should refrain from this atrocious act. However, if no substantive assumptions about the nature of practical rationality are made, we may be able to arrive at any possible normative reason for action, given fundamentally different aims and desires of an agent in question, even after having full information and having engaged in flawless rational deliberation. This is not to be confused with the impossibility of any convergence among agents’ normative reasons. Even for the Humean, we might postulate a normative reason that “one ought to refrain from randomly stabbing people on the way to work”, for a set of agents. Convergence on normative reasons, for the Humean, would be a matter of empirical facts regarding the subjective motivational sets of agents, not a conceptual truth of practical rationality. That is why Humeans cannot evade the following valid argument for the moral error theory that was postulated by Joyce as a refined reading of Mackie:

1. If x morally ought to Φ, then x ought to Φ regardless of whether he cares to, regardless of whether Φing sastisfies any of his desires or furthers his interests.

2. If x morally ought to Φ, then x has a reason for Φing.

3. Therefore, if x morally ought to Φ, then x has a reason for Φing regardless of whether Φing serves his desires or furthers his interests.

4. But there is no sense to be made of such reasons.

5. Therefore, x is never under a moral obligation. – Richard Joyce (2001, p. 42)

The first premise (1) of this argument captures what Joyce (2001) calls the authority and inescapability of morality. Whenever we make a moral judgement on a rapist or a Nazi responsible for the Holocaust, we do not alter our judgement regardless of what the culprit may cite as his desires or goals. Otherwise, as we noted above, a normative system recalling such judgements would not deserve to be called morality. Furthermore, we also elaborated Mackie’s Platitude (2): the position that moral judgments need to backed by some kind of special authority, a normative reason which can only be provided by practical rationality, in order to make morality stand out from all other normative systems that we could imagine, among them Nazi ‘morality’. We are here not asking for a moral reason speaking from inside the institution of morality, but a normative reason that can only be provided by practical rationality, in order to have the special authority morality requires. (3) merely follows from (1) and (2), and it is here that the Humean diverges from the non-Humean. Someone making the claim that “x has a reason for Φing regardless of whether Φing serves his desires or furthers his interests” must accept that there must be some sort of convergence among agents’ normative reasons. However, the acceptance of the latter is simply the denial of our Humean conception of normative reasons.

Notably, this should not be confused with Williams’ (1981) argument for internal reasons. Smith (1994) also argues for the thesis that there are only internal reasons, but goes further to state that they will converge for “rational agents”, thus making moral objectivity possible. How this should be possible without substantive assumptions about rational deliberation is questionable. As a consequence, Humeans must accept that no sense can be made of such reasons (4), as they imply that the goals of different agents will universally converge. Thus, Joyce (or rather, his reading of Mackie) provides an argument for why Humeans must accept that an agent X is never under a moral obligation (5). Every obligation we would like to postulate, such as “you ought not to torture babies”, would lack the special authority that morality must necessarily possess.

As we have thus shown in this section, Humeans cannot deny the conclusion that there are no moral obligations by attacking (4). Accepting the non-convergence of normative reasons directly implies (4). Therefore, Humeans must see, as Kant anticipated, the set of duties and obligations (i.e. categorical imperatives) as an empty concept. As categorical imperatives (i.e. universalized obligations) are a necessary property of morality, morality also becomes an empty concept and the error theorists’ case for second-order moral nihilism is made. But before we turn to our case for first-order moral nihilism, let us first deal with a potential objection by Bernard Williams, as someone operating within a Humean framework.

Potential Objections

The argument Williams provides against moral nihilism is an argument that not only has support among philosophers, but also those parts of the general population who do not buy into a strongly realist reading of moral discourse. For Williams, the error theorists’ (or for that matter, the moral rationalists’) view of moral obligations (1) is unacceptable.

[A sense of obligation that derives its reason externally] would seek to ‘stick’ the ought to the agent by presenting him as irrational if he ignored it, in a sense in which he is certainly concerned to be rational. I doubt very much, in fact, whether this proposal does capture what the ordinary moral consciousness wants from the ought of moral obligation, as opposed to something read into it by a rationalistic theoretical construct (it could be – though I doubt it – that this is what Kant wanted of the misleadingly named ‘Categorical Imperative’). But if this were what was wanted, there would be good reason to see moral obligation as an illusion. – Bernard Williams (1981, pp. 122-123)

Notably, Williams agrees that the moral rationalists’ desire for categorical imperatives is doomed and would lead to moral obligations being seen as nothing more than illusions, but instead of endorsing a moral error theory Williams argues against seeing morality as something independent of an agent’s motivational states. Trying to close the direct pathway to moral nihilism, Williams argues that it is a mere accident that the moral ought often coincides with the ought of practical deliberation. It is not the categorical imperative that gives morality its authority and force, but the mere empirical fact that “a fair proportion of agents a fair proportion of the time grant [moral considerations] force in their deliberations” (Williams 1981, p. 120). Morality has force because a fair number of agents simply assign weight to moral considerations in their practical deliberations, similarly to how checkers players care about playing by the rules. Williams is right to insist on the claim that one only ought to behave in accordance with morality conditional on having appropriate mental states. However, a position that says morality only has normative force if doing so corresponds to the self-interested pursuit of one’s aims and desires does not seem to capture how we usually think of morality; even within Hume’s own description of morality as a mixture of social conventions and our moral psychology that favours cooperation (see also Veit 2019).

Mackie’s denial of moral facts rests on the plausible assumption that moral facts in the form of categorical imperatives conceptually provide nonrelative normative reasons for agents regardless of their subjective motivational set. If there are no such non-relative normative reasons, then moral judgements stand on equal footing with the condemnation a beginner would receive for making an illegal move in a game of checkers. The authority of condemnation “you ought not to have done that” would rest solely on the empirical fact that you and your partners actually want to follow the rules. The response of a cheater that “I don’t care about the rules of checkers” would then be just as appropriate as the response “I don’t care about morality”. Though distinct in their content, there would be no intrinsic difference between the normative force of morality and the rules of checkers, etiquette, or Nazi law, since it is only the normative weight that different agents assign to them in virtue of their own desires that gives them their force. If Williams’ concept of morality commits us to the view that moral judgements such as “you ought not to torture innocent children for fun” are false provided the culprit has an appropriate subjective motivational set, one may justifiably ask what then the purpose of morality is, if not to provide inescapable authority. Williams’ view becomes even less attractive when we consider a world where 99 percent of the population are Nazis. In this thought experiment Williams is left with two implausible responses: either conceding that morality would now simply consist in what ‘Nazi morality’ consists in, or accepting the view that ‘Nazi morality’ provides more normative force than our cherished moral values.

Since no one seems to want to accept the second option, this conflict between different Humean philosophers appears largely to be one of moral nihilism versus moral relativism. One of our reviewers, for instance, noted that they believe moral relativism to be the best reading of Hume’s own views and those of the majority of Humean thinkers. But even if this were true, we would like to urge them to bite the bullet of moral nihilism for the sake of internal consistency. Relativism doesn’t provide us with a satisfying intermediate between universalized moral imperatives and moral nihilism, precisely because even within particular cultures there wouldn’t be anything resembling a categorical imperative. If Williams’ conception of morality allows that some agents simply do not have a reason not to torture children for fun, or worse ought to torture children, this is a prima facie ground to reject calling such a conception morality at all. Accepting the folk theory of morality, i.e. the alleged existence of objective mind-independent reasons for moral actions, commits the Humean to a moral error theory, for no sense can be made of such reasons.

As Joyce (2018) points out, “[...] one’s reason to move a chess piece in a certain manner exists only in virtue of some human-decreed system of rules. But moral rules, according to Mackie (1977), have their reason-giving quality objectively; we do not treat them as norms of our invention, for to do so would rob them of their practical authority, which is, arguably, their whole point” (p. 719), something Kant very much feared as a result of Hume’s work. The set of categorical imperatives would indeed be empty. This need not be a problem, as highlighted by most Humeans, since most agents in most situations will have prudential reasons to ‘make the moral choice’. And this is why we shall argue in the following section that an embrace of first-order moral nihilism need not be feared.

3 The Humean Case for First-Order Moral Nihilism

Making a case for first-order moral nihilism may seem almost irrelevant, given that ‘moral nihilism’, as it is understood in the general public, groups these two views firmly together. How, after all, could one seriously continue to use moral language and thought after accepting that morality is a deeply erroneous concept? As Garner (2007) nicely puts it at the end of his defense of moral abolitionism: “What serious philosopher can long recommend that we promote a policy of expressing and supporting, for an uncertain future advantage, beliefs, or even thoughts, that we understand to be totally, completely, and unquestionably false?” (p. 515).

Yet, the majority of error theorists appear concerned that the denial of the existence of moral facts would breed socially unwanted behaviour. They have thus tried to endorse more moderate positions, such as a conservationist or fictionalist stance towards moral discourse, which may explain why second-order nihilism doesn’t get as much serious philosophical attention as other meta-ethical views. Joyce’s fictionalist stance in particular, seems very much motivated in response to the fear that becoming an error theorist would make one’s action worse for both oneself and for others, and the popularization of his fictionalism has made the moral error theory a significantly more palatable position in meta-ethics. Whereas most thinkers previously assumed that second-order and first-order nihilism would go together, the growing literature on the ‘now what’ problem of the error theory (Lutz 2014) is very much motivated by exploring alternative positions to eliminativism. But while this embrace of a greater plurality of alternatives may well be an admirable goal, it has also led to a comparative neglect of moral abolitionism as a serious contender worth developing.

In his book on moral error theory, Olson (2014) dedicates a mere two and a half pages to rejecting the view, by stating the morality appears to be i) on balance beneficial and ii) hard to get rid of, since moral judgements are largely based in emotions (pp. 179-181). But this response is simply begging the question, restating, in no insightful sense, the obvious folk responses to moral abolitionism and instead appearing to endorse a conservationist stance. Joyce (2001) is skeptical of this move, one that is also found in Mackie, and instead treats fictionalism as a mid-level approach between abolitionism and the status quo. This approach may be disadvantageous - both collectively and for the individual error theorist adopting a fictionalist stance - but might nevertheless be better than giving morality up altogether. This fear of first-order moral nihilism could thus be countered if we can provide reasonable arguments showing that the abolition of moral talk won’t cause problems, and that moral talk isn’t anywhere near as conducive to the pursuit of the goals of the members within a society as is typically assumed. If this can be shown, there appears to be little reason to imitate Plato in trying to maintain morality through ‘noble lies’.

The Disutility of Morality

That morality is advantageous is perhaps the most unquestioned assumption within the entire domain of ethics. So it is unsurprising that error theorists have addressed the ‘now what problem’ in such a way as to try and avoid the abolition of morality. Even Mackie (1977) notes at the end of his book that “In so far as the objectification of moral values and obligations is not only a natural but also a useful fiction, it might be thought dangerous, and in any case unnecessary, to expose it as a fiction”, though then immediately admits that this can be challenged, since even a society of error theorists would have to “find principles of equity and ways of making and keeping agreements without which we cannot hold together” (p. 239).

Whereas Mackie does not want to throw the baby out with the bathwater, the moral abolitionist is convinced that the very core of moral discourse – objectifying moral values and obligations - is harmful to human wellbeing and requires an eliminativist stance. This can be considered to be similar to how other harmful cultural practices, such as Chinese foot-binding and female genital mutilation, can be challenged on the grounds that we’d be better off without them in a nonmoral and merely prudential sense of the term. This abolitionist stance is thus not only about the employment of moral categories in thought and language by the error theorist himself, but about the general aim of abolishing morality.

That morality - in the sense of a society believing in the objectivity of their most cherished values and that anyone opposing them should be considered akin to ‘evil’ - could be harmful and should thus be abolished, has been argued early on by Hinckfuss (1987). Indeed, he aimed to challenge the view of those critical of the alleged objectivity of moral values - such as Protagoras, Hobbes, Hume, and Mackie[3] - who uncritically believed that morality as a social phenomenon nevertheless improves social cooperation and wellbeing. He did so in a manner that could almost be seen as akin to mocking the very idea:

[T]he massacre of the moral Catholic highlanders by the moral Protestants at Culloden and its aftermath, the genocide of the peaceful and hospitable stone-age Tasmanians by people from moral Britain, the mutual slaughter of all those dutiful men on the Somme and on the Russian front in World War I, the morally sanctioned slaughter of World War II, especially in the area bombing of Hamburg, London, Coventry, Cologne, Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the subsequent slaughter in Korea, Vietnam, Northern Ireland and the Middle East – all this among people the great majority of whom wanted above all to be good and who did not want to be bad. If life in a ’state of nature’ was less secure than this, things must have been very exciting indeed for our stone-age ancestors. – Ian Hinckfuss (1987, §2.2)

Whereas we are happy to see the good that morality brings about, its negative consequences are excused, explained away as not really having followed from the right actions. Joyce (2001) exemplifies this, responding to Hinckfuss that he wonders “how much the specifically moral convictions should be blamed for such events, and suspect that the carnage would have occurred even without the backing of moral rationalizations” (p. 180). But can we sensibly deny that moral thinking played a major part in justifying the events described above?

We strongly disagree with Olson’s dismissive attitude towards this motivation for first-order moral nihilism through drawing on the suggestion by Warnock (1971) that such arguments are “scarcely more than an exaggeration of a point that is perfectly familiar and unsurprising—namely, that both individuals and groups are somewhat prone to consider, quite sincerely if self-deceivingly, as requirements of morality what suits themselves” (p. 156). The argument of the moral nihilist isn’t just that moral talk is often used in a self-serving way, but rather that moral thought and language leads to more extreme actions, such as wars, that make everyone worse off.

Not unlike religion, under morality actions are taken not because they serve the ends of members of our society, but because they are right and must be done; with the exception of the comparatively few consequentialist utilitarians that are out there in the world. Given that most oppose consequentialist thinking, why should we have any confidence in Olson’s “suspicion [...] that moral discourse is at least potentially more beneficial than detrimental to human and non-human well-being” (2014, p. 180)? A desire for revenge and punishment are deeply ‘moral’ emotions and should be seen as just as much at the core of our moral psychology as the pro-social emotions many of us admire.

Morality has plausibly been very important to ensure social cohesion in ancestral hunter-gatherer groups, but why should we think that morality has a net benefit for most people in our modern large-scale societies? Rather than providing us with means of settling conflicts of interest and between different values of different parties, moral thinking and language turns people into uncompromising partisans. As Garner (2007) notes, the “controversy over abortion would not be nearly as intractable as it has become if the fiction of moral rights had not been appropriated by both sides” (p. 502). Perhaps, Hume thought that morality provides a common grounding for the widely different interests of people to overcome their selfish desires, but more often than not the opposite appears to be the case. People objectify their own deeply cherished values, which are inevitably going conflict with those of others. To preserve the belief in an objective morality in the absence of moral truths will invite more conflict than its abolition ever could:

Not only does the moral overlay inflame disputes and make compromise difficult, the lack of an actual truth of the matter opens the game to everyone. Every possible moral value and argument can be met by an equal and opposing value or argument. The moral overlay adds an entire level of controversy to any dispute, and it introduces unanswerable questions that usurp the original question, which is always some practical question about what to do or support. This “moral turn” guarantees that the participants will be distracted from the real issue, and that the disagreement will flounder in rhetoric, confusion, or metaethics. The dangers of the moral overlay are far worse than Mackie thought. – Richard Garner (2007, p. 502)

Hinckfuss was right to question the supposed benefits of ‘the moral society’, which are undermined by the widespread differences in the moral values people hold. What would be admittedly difficult problems to solve in mere conflicts of interest between different parties, become unsolvable moral disputes in which the other side is simply dismissed as ‘wicked’ and any concession ‘immoral’. That moral nihilism isn’t the great ‘evil’ it is made out to be will become even clearer once we closely examine the assertion that it could not be implemented.

The Possibility of Abolishing Morality

Even if thinking in terms of moral categories and the employment of moral language has negative effects for both society and individuals in their attempts to settle conflicts, we still may be opposed to first-order moral nihilism on the simple grounds that our evolved moral emotions are simply too deeply entrenched to be overcome. Olson (2014), for instance, dismisses abolitionism as quickly as Johnson dismissed idealism by kicking a stone: “Given that moral thought and talk are to large extents based on emotions, and given the significant roles they play in social and personal human life, it would be exceedingly difficult to abolish moral thought and discourse” (p. 181). We suspect that most Humeans of the non-cognitivist bend hold such a position in regards to morality, seeing it as nothing over and beyond our shared collective moral sense. But here we should not confuse moral nihilism with the position that we should abolish all of our moral emotions.

Just as the atheist is not trying to rid people of their sense of wonder and purpose in the natural world, or the neuroscientist trying to convince his husband that love is an illusion foisted upon us by our brain chemistry and not reflective of a magical spiritual connection, there is no need for moral nihilists to abolish their sense of care for others. Contrary to popular opinion, nihilists can be just as sociable as moral realists - perhaps more so, since they try to take the perspectives of others, rather than judge their values as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. Sommers and Rosenberg (2003) on the surface seem to be happy to endorse such a view, calling it nice nihilism, but they say little of how a widespread adoption of moral nihilism would look in practice. Nevertheless, their point that self-avowed nihilists can perfectly well be nice people is well taken.

What the moral nihilist urges, is the abolition of the objectification of values, i.e. to put an end to what Hume described as the projection of our subjective values onto nature. And this can certainly be done, as Hume himself acknowledged. Moral nihilism isn’t akin to asking people to give up their taste and likes for particular sorts of ice cream, but merely asking them to recognize that their moral preferences are no different in kind from other sorts of subjective evaluations. Given how widespread anti-realist views are in the general public, we have no doubts that this move can be made: after all, we and other moral eliminativists such as Hinckfuss and Garner have done so successfully.

Philosophers have spent too much time on mystifying morality, and philosophers in the tradition of Protagoras, Hume, and Mackie have continually sliced apart the knots made by moral realists. Religious leaders have often maintained that atheists could possibly destroy the awe of nature, and yet, atheism has successfully grown, leaving old dogmas behind. We urge philosophers who accept the status quo without critical examination to seriously question their position. Philosophy cannot and ought not to exist as a mere tool to vindicate our existing dogmas and beliefs, be they even our most cherished values. In the absence of serious counterarguments against first-order moral nihilism, we should treat it as the natural consequence of second-order moral nihilism, without using this as a reason to discount the meta-ethical view. To do so, would be to confuse the modus ponens for a modus tollens. That moral abolitionism does not fit with the widespread implementation of our own preferred values, or the sense of importance we associate with them, can neither be used as an argument against first-order nor second-order moral nihilism.

4 Conclusion

Joyce (2013) once suggested that the best-defined usage of moral nihilism would be to treat it as a synonym for the moral error theory, but maintained that “even here, one is tempted to think that it would be safer simply to drop the term [...] since it is, as we have seen, pregnant with vague associations – associations that should be kept in abeyance until this imagery can be made more precise and its connection to the moral error theory shown to be justified” (p. 4). The goal of this paper was to show that we can reclaim ‘moral nihilism’ as the most consistent view to take within a Humean framework in moral philosophy, effectively combining both a second-order moral error theory and a first-order moral abolitionism. That is, we argued, the way moral nihilism should henceforth be understood, as a position which also closely mimics public thinking about moral nihilism, though without the implication that moral nihilists must be pursuing their own self-interest at all costs without care for others. Just as has been done for the word ‘queer’, we hope to change the negative connotations of ‘moral nihilist’.

To conclude, the moral rationalist’s conception of morality as requirements of rationality (i.e. as a set of categorical imperatives) elegantly captures the properties of inescapability and authority of moral judgements; in short that they are universalizable. However, Joyce was right to argue that a Humean conception of normative reasons conceptually rules out practical rationality as a solution against moral nihilism. For any moral ought-statement in the form of a categorical imperative, we would require normative reasons that hold for the agent regardless of his desires and aims. But as we know since Hume, normative reasons lack convergence among agents, hence rendering us incapable of defending categorical imperatives. Kant’s fear of the emptiness of his concept of categorical imperative is genuine and he can thus perhaps be considered the first philosopher to conceive of a moral error theory. Even though he ended up refuting the notion that the concept of duty is an empty one, it was his argument that eventually led a Humean – that is J.L. Mackie - to articulate the position.

If all moral beliefs are fundamentally mistaken, we should openly and critically investigate the possibility of a ‘society free of morals’. Philosophers should not be able to refute moral nihilism by merely asserting that they find the position psychologically hard to adopt and potentially dangerous. Firstly, we urge fellow error theorists to seriously try to eliminate moral talk from their own thinking and observe what happens. We doubt this shift will be any more difficult than the painstaking shifts from those who leave the Church after having spent decades in it. Secondly, error theorists can’t use the lack of evidence of current nihilist societies to conclude that morality is beneficial overall. At most, they should urge caution and stay neutral, but this would then require a more serious investigation of moral nihilism than has hitherto been offered. Practical benefits aside, we hope that the present paper has shown that the right Humean response is to become moral nihilists twice over and commit morality to the flames, for it contains nothing but sophistry and illusion. To do otherwise is to continue with an unfortunate - and for philosophy, uncharacteristic - respect for tradition, as if we could not justifiably become atheists prior to conclusively debunking all conceivable arguments for the existence of God. We thus hope that the insult ‘moral nihilist’ can be reclaimed similar to terms such as ‘atheist’ and ‘queer’.

References

Blackburn, S. (1993). Essays in Quasi-Realism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bourget, D. and D. J. Chalmers (2021). Philosophers on Philosophy: The PhilPapers 2020 Survey. Preprint.

Foot, P. (1972). Morality as a system of hypothetical imperatives. The Philosophical Review 81(3), 305–316.

Garner, R. (2007). Abolishing morality. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 10(5), 499–513.

Garner, R. T. (1990). On the genuine queerness of moral properties and facts. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 68(2), 137–146.

Hinckfuss, I. (1987). “The Moral Society: Its Structure and Effects”. In Discussion Papers in Environmental Philosophy. Canberra: Australian National University.

Hume, D. (1748). An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/9662/9662-h/9662-h.htm [accessed February 23, 2012].

Joyce, R. (2001). The myth of morality. Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, R. (2013). Nihilism. In H. LaFollette (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Ethics, pp. 147–171. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

Joyce, R. (2018). Moral Skepticism. In D. Machuca and B. Reed (Eds.), Skepticism: Antiquity to the Present, pp. 147–171. London: Bloomsbury. Kant, I. (1783). Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals [1985 Edition, Translated by H.J. Paton]. London: Hutchinson.

Kolodny, N. (2005). Why be rational? Mind 114(455), 509–563.

Korsgaard, C. M. (1996). The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lutz, M. (2014). The ‘now what’ problem for error theory. Philosophical Studies 171(2), 351–371.

Mackie, J. L. (1977). Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong. New York: Penguin Books.

Olson, J. (2014). Moral Error Theory: History, Critique, Defence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons. Oxford University Press.

Smith, M. (1994). The Moral Problem. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sommers, T. and A. Rosenberg (2003). Darwin’s nihilistic idea: evolution and the meaninglessness of life. Biology and Philosophy 18(5), 653–668.

Veit, W. (2018). Existential Nihilism: The Only Really Serious Philosophical Problem. Journal of Camus Studies, 211–232.

Veit, W. (2019). Modeling Morality. In Angel Nepomuceno-Fernándéz, L. Magnani, F. J. Salguero-Lamillar, C. Barés-Gómez, and M. Fontaine (Eds.), Model-Based Reasoning in Science and Technology, pp. 83–102. Springer.

Warnock, G. (1971). The Object of Morality. London : Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Williams, B. (1981). Moral Luck. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[1] We dedicate this article to the recently deceased Garner, for convincing us of moral abolitionism in the first place.

[2] If only practical rationality can provide practical reasons, then there are no practical reasons.

[3] See Veit (2019) for a philosophical analysis of attempts to put their arguments into the form of evolutionary models.

The original paper is here:

Veit, W. (2024). Reclaiming Moral Nihilism. Revista de Filosofía. https://doi.org/10.5209/resf.91005 [Download]

Outstanding argument on the disutility of moralizing languageitself. The abortion example is spot-on, moral facts peoplecreate impasses where preference-stackers would just talk tradeoffs. I worked on policy debates where invoking rights frameworks basically nuked any chance at pragmatic middle ground, people assumed we were arguingabout cosmic truths instead of resource allocation.

I stumbled into this arcane debate via BS Brigade’s posts. Reading his posts and others I then encountered led me to the strong view that there is no good case for moral facts.

I could well be wrong. My main point is I cannot see how it matters.

Fact or preference - the fact advocates struggle to present a useful set of agreed such facts. Ones that would guide action on relevant matters.

I have used abortion as an example of something relevant. There are numerous coherent cases made that abortion is/is not OK. I cannot see that both outcomes can be facts - if only one is a fact how is that determined?

I say my position is my judgement.

What I get from the moral facts people is a need for certainly. They struggle with saying ‘I may be wrong but this is what I think I (or even other people) should do”.